Let me paint a picture for you, one that a lot of pitmasters will be depressingly familiar with.

It’s the weekend. You’ve laid your hands on a pork shoulder or a prime beef brisket, and you’ve invited your friends and family over to enjoy it with you.

You fire up your smoker, using the Minion Method, stabilize the pit temperature and sit back to enjoy a well-earned beer.

The meat temperature climbs for the first few hours, giving you that warm feeling of accomplishment, and then it flatlines. Perhaps, to your horror, the meat even starts to drop in temperature.

Your guests are getting hungry, all eyes are on you, and your promised meat is actually creeping away from that magic 203°F mark.

Welcome to stall town!

The good news is that the BBQ stall is not a divine punishment handed down by the Pit Gods It’s just chemistry and there is a solution to it.

In this article, we’ll go over what causes the BBQ stall and your best options to beat it.

What is the barbecue stall, and why does it happen?

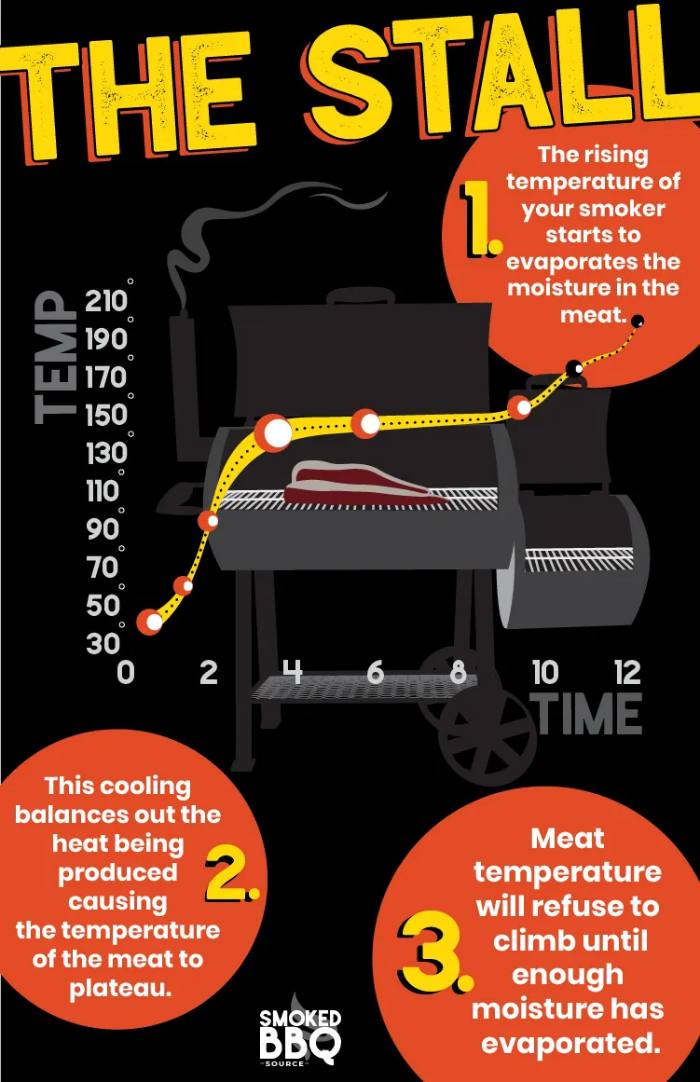

The barbecue stall is what happens after you place a large piece of meat, like brisket, on the smoker and after two to three hours the temperature of the meat hits about 150°F and stops rising.

The stall can last for up to six hours before the temperature starts rising again.

There are a fair number of different theories floating around about why certain meats stall during cooking.

Thankfully, the teams over at Amazing Ribs and Genuine Ideas decided to conduct a variety of tests to determine precisely what was happening to cause the stall.

Their test showed that the most likely culprit for the stall was evaporative cooling.

To put it simply, while you are sweating because your meat isn’t coming up to temperature, your brisket or shoulder is doing the same thing.

After about three hours of cooking, the rising temperature of your smoker evaporates the moisture in the meat.

This evaporative cooling balances out the heat being produced by your smoker’s fuel, causing the temperature of the meat to plateau, usually at around 150°F.

This is the same process that keeps your body cool by causing you to sweat on a hot day.

The stall may begin at an internal temp that’s anywhere between 150 and 170°F, depending on the particular piece of meat (size, shape, surface texture, moisture content, injection, and/or rub) and the cooker (gas, charcoal, logs, pellets, airflow, water pan and humidity),

Meathead Goldwyn – amazingribs.com

The temperature of the meat will then refuse to climb again until enough moisture has evaporated that evaporative cooling cannot offset your smoker’s heat.

Three common stall misconceptions to avoid

The cause of the stall has been debated in pitmaster circles since we first noticed it was happening.

The problem is that a lot of the theories that cropped up, and their proposed solutions, were focussing on the wrong culprits.

With multiple experiments showing that evaporative cooling is responsible for the stall, here are a few older misconceptions that have been myth busted.

1. The stall is caused by latent heat lipid phase transition

It’s a bit of a mouthful, right?

In layman’s terms, the latent heat lipid phase transition is when the collagen in your meat combines with water and changes into gelatin.

This transition is an integral part of the cooking process, as the rigid structure of the collagen transforms into soft flavourful gelatin.

The latent heat lipid phase transition also occurs at about 160°F, exactly when the stall normally starts.

This led to pitmasters, understandably, to blame the transition for the stall.

However, collagen only accounts for about 2% of the overall structure of your meat. There just isn’t enough collagen in your brisket or pork butt to offset the heat of your smoker as it transitions to gelatin.

2. The stall is caused by protein denaturation

At between 140°F and 150°F, proteins in the meat start to denature.

Denaturation is a process proteins undergo when exposed to sufficient heat.

The heat energy causes them to unfold from a complex 3D shape into a looser arrangement. This enables them to more easily combine with other substances, such as water, in your meat.

This transition does happen, and at around the same temperature as the stall typically starts. However, there isn’t enough protein in your meat for it to offset the heat energy produced by your smoker.

3. The stall is caused by fat rendering

On the surface, this theory seems more viable than the protein-based methods.

A pork shoulder is about 15% fat.

The team at Genuine Ideas tested this theory by cooking a chunk of pure beef fat and a cellulose sponge soaked in water in the same oven.

They then monitored the temperatures to see if the rendering of the fat cause it to stall. Their results overwhelmingly disproved this theory.

The fat continued to rise in temperature as expected, while the sponge hit a heat plateau at just under 150°F, stalling just like you would expect a cut of meat to do.

This because the fat simply melted, rather than evaporated, a process that uses far less thermal energy.

What types of meat/cuts are most affected by the stall?

Unfortunately, avoiding the stall isn’t as easy as choosing another piece of meat to cook.

Evaporative cooling, the cause of the stall, is down to two things: The fact that most meat is about 65% water and the low and slow cooking process.

The combination of the size of the piece of meat you’ll be cooking, the low temperature and the high water content makes the stall a part of the cooking process.

The stall is especially feared when cooking a brisket or pork butt.

How long can the stall last?

For brisket, the stall normally starts after two to three hours once the internal temperature of the meat is around 150°F. The stall can last for as long as 7 hours before the temperature of the meat starts to rise again.

Once the temperature does start to rise, it can go quickly. It’s common for a brisket to make the final jump from around 170 – 203°F in an hour or two.

Moisture evaporating from the meat will then stall its temperature out, with the stall moving from the outer surface to the center.

This stall will continue until enough moisture has evaporated away that it cannot balance the thermal energy produced by your smoker. The temperature of your meat will then start to climb again.

The length of your stall is hard to predict, as it depends on a large number of variables:

- The size of the cut of meat you are trying to cook – The larger the piece, the more water it will contain and the longer it can stall for. The surface area of the meat also contributes. A large surface area will result in greater evaporation of moisture

- The design of your smoker – Smokers with greater airflow encourages evaporation. Some pellet smokers may even have a fan in them, which can contribute to a shorter stall. Electric smokers also tend to be well sealed, which reduces evaporative cooling

- Using a water pan – Water pans keep the humidity inside your smoker high, preventing some of the moisture loss during cooking. They also allow water to mix with the smoker on the surface of your meat, increasing the smoky flavor. The downside is that they add to the moisture on the surface of the meat, extending that stall time

- Using a wet mop/brush/spritz – A lot of pitmasters add moisture to the surface of their meat while it cooks, using a variety of techniques. This has the same benefits as the water pan but also slows down the cooking time by adding to the stall

With all these variables, it’s hard to put an exact time on how long a stall might take.

According to Murphys Law, the stall will probably take about an hour longer than you estimated.

In some really extreme cases, I’ve heard of brisket stalls lasting for over 10 hours!

How do I beat the stall?

The good news is, now we understand why the stall happens, there are ways around it:

Option 1: Start early and rest your meat until ready to serve

This is your best option. Once you know that the stall is part of the cooking process and you know to expect it, you can prepare for it.

Although it can feel like nothing is happening and something must be wrong, the stall means everything is going as expected.

Moisture is being evaporated from the surface of your meat, inside it is mixing with rendered fat and denatured proteins, keeping your meat nice and moist.

So how do you make sure your brisket is ready to serve at an exact time?

The key is to start early enough that the meat will definitely be finished at least an hour before you need to eat.

Once your meat hits the correct temperature, take it off the smoker.

You can then wrap the meat (still wrapped in foil or butcher paper) in a few old towels and leave it in a cooler to keep warm for up to 3-4 hours.

The exact amount of time you can store meat safely will depend on how well insulated your cooler is.

Related – The best soft-sided coolers

The faux cambro method has the added advantage of allowing the meat to rest and relax.

When I started using this method it was a total game-changer. Now I always have the meat ready a few hours before guests want to eat, and that leaves me free to work on sides or to socialize and drink a few beers (or smoked cocktails!)

Option 2: Use the Texas Crutch

The Texas Crutch is a way to beat the dreaded stall by wrapping your meat tightly in aluminum foil.

Sometimes you could also add extra moisture in the form of beer or fruit juice.

Pitmasters have been using the Texas Crutch for years on the understanding that wrapping and extra moisture creates steam which speeds up the cooking process.

While the method does work, the actual reason it works is that the foil prevents the evaporative cooling.

Wrapped in foil, the moisture escaping the meat isn’t carried away. It condenses on the inside of the foil, pooling at the base of the meat.

Without evaporative cooling to reduce the temperature, the stall just doesn’t happen.

Think of it like running in your raincoat, or trying to sleep through a hot night in a cheap plastic tent.

You’ll certainly be sweating, but you sure as hell won’t be getting any cooler.

The downside of the Texas Crutch is the very thing that makes it useful in beating the stall.

By trapping moisture next to the surface of the meat, the Texas Crutch makes it almost impossible to build up that dark crispy bark that a lot of brisket lovers crave.

How to wrap your meat for the Texas Crutch

- Smoke your meat for around two-thirds of its total cooking time, allowing the bark to reach a color that you are happy with.

- When your meat hits the stall, at around 150-160°F and refuses to climb any higher, remove it from the grill.

- Wrap your meat in at least two players of heavy-duty foil. Before you seal it up.

- Make sure the seal on your foil is tight. The idea here is to let as little moisture escape as possible in order to cut down on the evaporative cooling effect.

- Return your tightly wrapped meat to your smoker, and you should see it break out of the stall as the temperature starts to rise again

- If you want to try and get as much bark as possible, remove the foil when the meat reaches your target temperature and put it back on the smoker so the bark can firm up.

Option 3: Use the butcher paper method

Not all pitmasters are going to be happy with putting a foil barrier between their meat and the smoke.

If you want a solution that can help you beat the stall while not entirely sealing off your meat, you can use pink butcher’s paper.

Unlike foil, butcher’s paper is porous. This means that the smoke can permeate the paper and get to the meat underneath.

The downside of using butcher’s paper is that it does not create enough of a seal around the meat to completely avoid the stall. You may find your meat still stalls out, but it will be for a much shorter time compared to non-wrapped meat.

Aaron Franklin is famous for using pink butcher paper. You can check out a brisket wrap test he did in the video below where he compares unwrapped, foil wrapped and paper wrapped brisket.

If you are interested in trying the Texas Crutch, or want more info on how exactly to wrap your brisket, we’ve written a whole article on it that you can find here.

Option 4: The Sous-vide method

Another method for beating the stall is to change your cooking method altogether. Instead of covering your chosen meat with aluminum foil or butcher’s paper, smoke it until the meat reaches the stall and then transfer it to a sous-vide.

Since cooking sous-vide involves you vacuum packing the meat, it solves the evaporative cooling issue in the same way a tight covering of foil does. It also gives you the usual sous-vide benefits of precision temperature control, consistent cooking, and the fact that the meat cooks in its own juices.

The downside of using a sous-vide is that it adds one more step to the cooking process, which some pitmasters might not appreciate, and it requires you to have a sous-vide set up.

If you’re skeptical, we have a guide about combining sous vide and barbecue for epic results.

Option 5: Cook it hot and fast

If you want to avoid the stall associated with low and slow cooking, one option is to flip the playbook and cook your meat hot and fast.

This method does not work with a brisket flat, as it will leave denser less fatty meat dry and tough. It will, however, let you cook a brisket point, which is fattier and contains more collagen, in around 6 hours.

How to cook a brisket point hot and fast

- Season a five to six-pound brisket point with salt and pepper

- Place the brisket point into a 400-degree smoker

- Wait till the internal temperature of your beef hits around 165°F. This should take about two and a half hours

- Once the meat is up to temp, transfer it into a roasting tin and put it, uncovered, into an oven preheated to 250°F

- Continue to roast the brisket point until the meat’s internal temperature comes up to 205°F

- Remove your brisket from the oven and let it rest at room temperature until the meat’s internal temperature comes back down to 140°F

- Slice your brisket against the grain and serve to the hungry masses

Bust that stall!

Now you know why the stall happens, you can put in place a plan to overcome it.

If you don’t have any particular time pressures, you can wait out the stall. This will help you get that good crispy bark.

You can use the Texas Crunch to put a halt to that evaporative cooling, punching right through the stall. If you still want more smoky flavor, simply switch out the foil for butcher’s paper.

You can even change the game altogether, opting to cook your meat hot and fast or use your smoker to flavor it before finishing it in the sous-vide.

The main thing is you no longer have to go into meltdown when you hit the stall, you know what’s happening and you know how to beat it!

Have you got any techniques that helped you beat the stall or any stall horror stories you’d like to share with us? We’d absolutely love it if you posted them in the comments below.