Browsing the meat section of your local supermarket or the menu at an upscale steakhouse can be a confusing experience.

You’re just looking for a good steak to eat, and you have to wade through a million different cuts, each with a dozen different names.

Then you have to sort through all the jargon and marketing.

Do you want dry or wet aged? Is domestic Wagyu better than Japanese Wagyu? Are a Porterhouse and a T-bone the same thing?

To help you become a steak pro we’ll be breaking down everything you ever wanted to know about steak, including the best steak cuts and how to cook them.

Steak 101

What exactly do we mean when we say steak?

At its most basic, a steak is any cut of meat sliced across the muscle fibers.

The word is occasionally used to refer to a thick cut of any type of meat, like pork steaks or cod steaks, or even certain vegetables, like cauliflower steaks.

While you can have steak from other types of meat, this article will focus on beef steak.

What part of the cow do steaks come from?

Different types of steaks can come from nearly any part of the carcass of a steer. However, there are four areas most commonly associated with beef steaks:

- The Rib – The Rib is the section of the carcass where the Delmonico, Tomahawk, and Ribeye are cut from.

- The Short Loin – The Short Loin is where the Top Loin, T-bone, New York Strip, Porterhouse, and Club Steak are cut from.

- The Sirloin – The Sirloin is where you’ll find, unsurprisingly, the Sirloin and Pin Bone Sirloin Steaks.

- The Tenderloin – The Tenderloin contains the sought after Filet Mignon and Chateaubriand steaks.

The top and center muscles on a steer’s carcass are prized because they don’t get much of a workout.

Since they aren’t used very much in the day-to-day life of the steer, the tissue remains tender.

This is particularly true of the Tenderloin, hence the name.

Why is steak so expensive?

The most expensive cuts of steak like the ribeye, strip loin, tenderloin, and T-Bone all come from the four areas of the carcass mentioned above.

You pay extra for the most tender steak thanks to a couple of reasons:

- Supply and demand – Steaks cut from the Rib, Shortloin, Tenderloin, and Sirloin have a reputation for being tender and flavorsome cuts of meat. This reputation, combined with the fact that these cuts are perfect for quick searing in a pan or grill using reasonably easy techniques, stokes demand and keep prices high.

- Scarcity – The Ribeye, New York Strip, Tenderloin, T-bone, and Porterhouse only make up about 8% of the total carcass of a steer. This low meat-yield keeps prices high for the most desirable cuts.

- Lack of knowledge about other cuts – Most people know what a Ribeye steak is and so are happy to order one in a steakhouse or buy one in the supermarket. Cuts like the Denver Steak, are less well known and people are less likely to purchase cuts of meat they are not familiar with.

It’s a bit of a misconception that anything marketed as “a steak” is going to be an expensive cut of meat.

Flat Iron steaks, Denver Steak, and Ranch Steak are all taken from the relatively inexpensive beef chuck section of the carcass.

They might take a little more effort to cook but, when prepared properly, they are still delicious cuts of meat.

The best steak cuts for grilling (or ordering at a steakhouse)

1. The Ribeye

The Ribeye is arguably the most iconic steak, and its reputation for flavor and tenderness is well deserved.

The longissimus dorsi muscle that the Ribeye is cut from doesn’t see much use during the steer’s lifetime, so the meat is very tender.

The Ribeye also has a good amount of marbling and that intramuscular fat renders down beautifully when appropriately cooked, adding to both the smooth texture and rich meaty flavor.

Where does it come from?

The Ribeye is cut from the upper ribcage of the carcass, generally between the 6th and 12th rib. The USDA grading system actually uses the Ribeye cut to grade the entire carcass.

The Ribeye is also known as:

- Entrecôte (in France)

- Delmonico (after the restaurant)

- Scotch fillet

- Spencer Steak

- Market Steak

- Cowboy Steak (with the bone in)

- Tomahawk Steak (with between 8 and 20 inches of the bone showing)

Cooking recommendations:

The Ribeye is a tender piece of meat with plenty of marbling, so it reacts well to hot and fast cooking methods like grilling and pan-searing.

The best ribeyes are cut 1.5-2 inches thick and are best prepared with the reverse sear method.

The amount of fat on a Ribeye can cause flare-ups, so be ready with a lid if your pan-searing it, or tongs to move it if you’re grilling.

2. The Strip Steak

A steakhouse classic, the Strip Steak is characterized by its medium level of marbling and the cap of fat that is found around its side.

The meat has a tighter texture than the Ribeye or the Tenderloin, ideal for those who want a little chew in their steak, and a pronounced meaty flavor.

Where does it come from?

The Strip Steak is taken from the loin, towards the rear of the same longissimus dorsi that produces the Ribeye.

Also known as:

- The New York Strip

- Ambassador Steak

- Country Club Steak

- Kansas City Steak

- Shell Steak (if served with the bone in)

- Top Loin Steak

- Hotel Cut Steak.

Cooking recommendations:

Much like the Ribeye, the Strip Steak takes well to being cooked over a high heat, be that pan-searing, broiling or grilling.

Because it lacks some of the marbling of the Ribeye, it’s actually easier to cook hot and fast, as it is less prone to flare-ups.

3. The Tenderloin

The most tender cut of meat from the carcass, the Tenderloin is a section of muscle that doesn’t see much use during the life of the animal, so the meat stays exceptionally tender.

It has a milder flavor than the Strip Steak and less fat than the Ribeye.

Where does it come from?

The Tenderloin Steak is cut from the thicker parts of the (surprise surprise) Tenderloin section of the carcass, located on the back and towards the haunches.

Also known as:

- Filet

- Filet mignon (when cut from the narrower end of the Tenderloin)

- Chateaubriand (when cut from the thickest end of the Tenderloin).

Cooking recommendations:

The thing that sets the Tenderloin apart from other steaks is its buttery-smooth texture, so you’ll want to avoid any cooking methods that could compromise that.

The best way to cook a Tenderloin is to sear it in a pan or a grill to create that all-important Maillard Reaction on the outside, and then finish it in the gentle heat of an oven.

Because it lacks the marbling of a Ribeye or the fat cap of the Strip Steak, the Tenderloin is often cooked with added fats, like butter, or wrapped in fattier meats, like bacon, to stop it drying out.

4. The T-Bone

The T-Bone is basically the best of both worlds, combining the Tenderloin on one side and Strip Steak on the other.

The two different pieces of meat are separated by the T-shaped bone that gives this cut its name.

Where does it come from?

The T-bone is cut from the Short Loin of the carcass, located at the top and center of the animal, just behind the ribs.

Are a T-Bone and a Porterhouse the same thing?

There’s no official distinction between a Porterhouse and a T-Bone steak, but generally, steaks sold as Porterhouse are cut from the rear of the short loin, and the T-Bones are cut from the front.

This means that a Porterhouse should have more Tenderloin and the T-Bone would have more Strip Steak.

The only official guidelines come from the US Department of Agriculture’s Institutional Meat Purchase Specifications and indicate that the Tenderloin section of a Porterhouse must be a minimum of 1.25 inches (32 mm) thick at its widest, but only 0.5 inches (13 mm) thick on a Tenderloin.

Also known as:

- Porterhouse

- Date Steak.

Cooking recommendations:

Because the T-Bone/Porterhouse has both Tenderloin and Strip Steak sections on the same steak, it needs a little more attention when cooking to stop one side from drying out or undercooking.

The best way to cook a T-Bone is by using a two-zone method. That way, you can turn the Tenderloin section away from the hot zone, preventing it from drying out, while still being able to cook the Strip Steak section properly.

Lesser-known types of steak you should know

The four steak cuts covered above represent the bulk of what you can get from the butcher or at a steakhouse.

If you limit yourself to the most common types of steak, you’ll be missing out on a world of flavor.

Get more steak for your dollar and impress your butcher by asking for one of these underrated cheap cuts of steak.

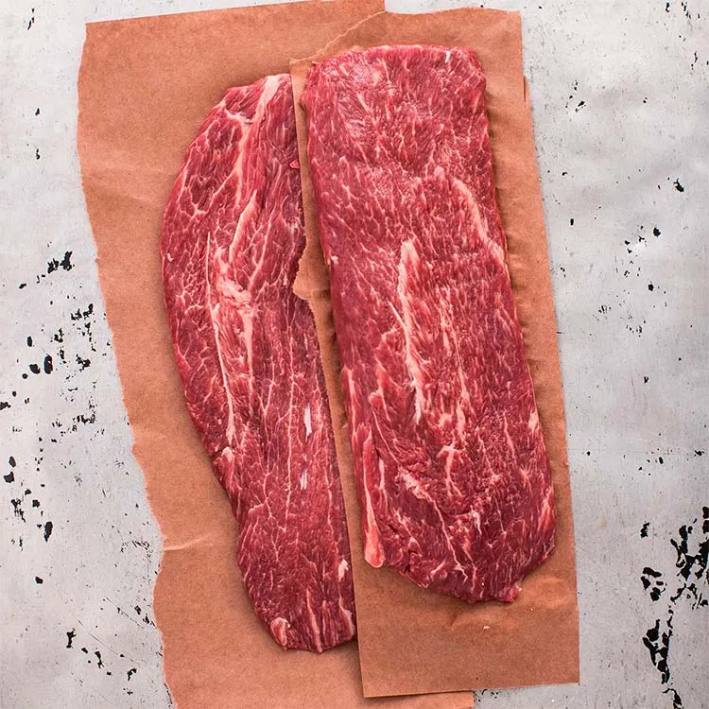

1. Flank steak

The flank of a steer is on the belly of the animal, close to the rear legs. Steak taken from this area is very lean and can get quite tough if not prepared properly. The Flank steak is a close neighbor of the Bavette steak and the two often get confused.

Flank steak is best cut against the grain, which is quite easy to do as the muscle fibers are very obvious.

Flank steak takes very nicely to rubs and marinades and is traditionally used in dishes where it is cooked hot and quick, like fajitas, stir-frys, and bibimbap.

2. Skirt steak

Often confused with Flank steak, the Skirt is actually the diaphragm muscle, which means it sees a lot of work during the animal’s lifetime.

The Skirt has a rich beefy flavor but a reputation for being chewy and tough if cooked incorrectly.

Much like the Flank steak, marinades and rubs are your friends here.

Skirt is the traditional cut for either fast sears, like in fajitas, or long slow cooks, like a good chili. One of the benefits of Skirt steak is that you get a lot of meat for your dollar, as the Skirt is a substantial piece of meat.

3. Hanger steak

Unlike the Flank or Skirt, the Hanger steak is one that you might find on the steakhouse menu.

This piece of meat gets its name from the fact that it “hangs” between the Tenderloin and the rib.

While nowhere near as tender as any of the cuts from the Tenderloin, the Hanger steak isn’t an active muscle in the same way that the Flank and Skirt are.

Its job is to support, not move, the diaphragm. This means the meat is far more tender than neighbor cuts, and it has a reasonable amount of marbling.

Hanger steak is traditionally used in dishes like Carne asada or Korean bulgogi but, if it sliced thinly and against the grain before being cooked to a medium-rare at the most, it can be served on its own.

4. Flatiron steak

The Flatiron is both an old and somewhat new cut of meat.

The cut itself comes from the chuck primal, or front shoulder section, of the animal and used to include a thick part of connective tissue which made it hard to do anything with.

In 2002, food scientists found a method, similar to filleting fish, to cut around this vein of connective tissue and created a cut of meat that rivaled the New York Strip for tenderness.

Since then, the Flatiron, so-called because the cut’s sharp tip looks like an old flat clothes iron, has become popular as a less expensive alternative to Strip Steak.

5. Tri-Tip steak

The Tri-Tip, known for its triangular shape, is taken from the bottom of the Sirloin Primal.

The Tri-Tip is lean and tender, with a good amount of marbling and a robust meaty flavor.

In many ways, the Tri-Tip is like a budget Ribeye.

It’s well marbled and well flavored if a bit leaner than cuts from the rib section.

Because of that leanness, cooking it to more than a medium-rare runs the risk of drying it out and one or two hours of marinating time can really help to keep the meat moist and tender.

Reverse sear method also works great for this cut. Check out our tri-tip recipe for detailed instructions.

Steak buying tips

Knowing the different cuts of steak is only half the battle. There’s a lot of other choices you’ll need to make when buying steak.

In this section, we’ll explain what the most common labels you’ll see on steak actually mean.

Grades of steak

Choosing a steak can be difficult for the untrained eye.

Thankfully the USDA grading system is a quick and easy way to identify the quality of the steak you are buying.

The USDA grades cuts of beef into one of three categories based on the degree of marbling and the age of carcass:

- Prime – Less than 2% of all beef in the US is graded as Prime, and USDA Prime certification is a food indication that the meat you are buying is both excellent quality and has between 8 and 13 percent intramuscular fat.

- Choice – Choice beef used to only be available through butchers, but there has been a significant rise in the number of supermarkets now stocking Choice graded beef. The Choice grading indicates good quality but a lower level of marbling, around 4 to 10 percent, than Prime beef.

- Select – Select beef is the most common grade of beef found in supermarkets and contains very little marbling, just 2 to 4 percent. Select grade beef also comes from younger cattle, those under 30 months, so may lack some of the flavors a similar Choice or Prime cut.

Wagyu & Kobe beef

Wagyu beef is meat taken from a specific breed of cattle that comes from Japan.

Beef cut from the Kuroge Washu, or Japanese Black, breed of cattle has exceptional marbling and a global reputation for melt in the mouth tenderness and a rich umami flavor.

Imported Japanese Wagyu beef is both expensive and rare, selling for $50 per ounce at the top end of the price range.

American Wagyu beef is available, although this is most commonly from cattle interbred with native strains, such as the Angus.

The USDA does certify some beef as Wagyu, but it only has to contain 46.875% pure Japanese blood to obtain that certification.

There’s a lot of confusion about the difference between Kobe and Wagyu, with the two terms used interchangeably.

Kobe Beef is ultra high-quality Japanese trademarked beef from the Hyogo prefecture that costs around $300 per pound and is sold by just 33 restaurants in the US.

You should probably avoid anything marketed as “Kobe Style” beef.

The “Kobe Style” beef indicates nothing about the quality of the beef or its origin and may as well be advertised as steaks cut from Kobe Bryant.

Dry / Wet Aging

You’ve probably seen steak labeled as “dry-aged” before. Usually with a highly inflated price tag.

So is dry-aged steak worth paying extra for?

Aging is a process undergone by nearly all commercially available beef.

It’s a form of carefully controlled decomposition that increases both the flavor and tenderness of the meat while ridding it of the metallic taste the meat can have when it’s freshly-slaughtered.

- Wet aging is the more common method of aging beef. It’s called wet aging because the beef is stored in a vacuum-sealed bag with its own liquids. Wet-aged beef doesn’t lose any of its weight due to moisture loss, but can sometimes have a slight mineral taste to it.

- Dry aging involves hanging cuts of beef in a temperature and humidity controlled environment for a period of up to several months. By hanging the meat and exposing it to a controlled environment, bacterial activity, enzyme breakdown, and oxidation can be used to tenderize the meat and increase its flavor.

Dry-aged beef tends to be more expensive than wet-aged beef for two reasons.

- Dry-aging results in moisture loss, shrinking the cut of meat and leaving less to sell, making it proportionally more expensive by weight.

- Unlike wet-aging, which only tenderizes the meat, dry aging both tenderizes and increases the flavor of the meat, making the end product more desirable.

If you have space and don’t mind investing in a few tools you can actually dry-age your own beef at home.

This video shows you the whole process and what gear you’ll need.https://youtube.com/embed/1o7GTADAo1g?feature=oembed

Grass-fed vs. Grain-fed

Some people, especially the more health-conscious among us, believe that grass-fed beef is better.

The actual debate is more complicated and nuanced. We have a full article that covers the difference between grain and grass-fed beef.

The problem is that the meat industry uses terms like grass-fed, grass-finished and grain-finished to mean different things.

For this article we will focus on the flavor differences.

“Grain-finished beef is known for marbling and tenderness because grain helps cows gain weight more quickly and reliably, and because grains just tend to produce a milder steak flavor. Grass-finished beef tends to have a beefier–sometimes called “gamier”–flavor because of the nutritional complexity of pasture grasses, and it also tends to be a little leaner.

Joe Heitzeberg – Co-founder and CEO of Crowd Cow

The demand for grass-fed cattle has risen in recent years, as some consider it to be a healthier option, even though some researchers have downplayed any real health benefits.

“A Texas Tech University study found no difference in cholesterol in ground beef from grass-fed and grain-fed cattle if the fat content is similar.”

Stephen B. Smith – Grass-Fed Vs. Grain-Fed Ground Beef — No Difference In Healthfulness

Grass-fed beef has two main potential benefits.

Depending on the supplier, grass-fed cattle may be raised more humanely and contribute less pollution than grain-fed animals.

It is important to note that simply being advertised as grass-fed in no guarantee of better rearing conditions so you still need to buy from a reputable supplier.

Grass-fed beef also has a distinctive taste that some people prefer to the richer, more buttery, flavor of grain-finished meat.

Where to buy steak

From your butcher

If you love steak and have a local butcher, go and make friends with them.

Like most professionals, a good butcher will be able to tell you things about the products that you are shopping for that you just can’t find anywhere else.

You can consult your butcher on what cuts of steak to serve and how to cook them.

You can also get their advice on lesser-known cuts, like Flatiron or Tri-Tip, and have your butcher trim and prepare you steaks in any way you want.

Looking for a Tomahawk steak so big you have to have an open carry permit to take it home? You butcher can sort that out for you.

From the grocery store

There was a time when you could only get great beef from your local butcher. Now you can pick up USDA choice steaks in your local Walmart!

If you are shopping for steak in a grocery store, you obviously aren’t going to get the same informed, personalized service you would in butchers.

The USDA grading system is going to be your best friend here, as the grading levels we talked about above are a great guide to the quality of beef that you are buying.

From an online supplier

Buying steak from the internet might seem like an odd idea, but there are plenty of reputable professional butchers on the internet who can have a whole range of specialists stakes delivered to your door in as little as 24 hours.

If you are struggling to find USDA Prime in your local area or you want to spoil yourself with some expensive imported Japanese Wagyu, an online supplier might be your best bet.

Some of our favorite websites for buying top quality meat include:

- Crowd Cow. – Great if you want to know about where your meat comes from and how it’s raised.

- Snake River Farms – Our favorite suppliers of domestic American Wagyu

- Holy Grail Steak Company – An impressive collection of authentic imported Wagyu and Kobe beef

If you are thinking about ordering steak online, check out our guide to the Best Mail Order Steak Companies before you do!

Tips for cooking steak

By now you should be a steak pro and know about all the factors that make a steak worth buying.

With a little practice and the right knowledge you can learn how to cook a steak that rivals anything you can get from an expensive steakhouse.

Use the “reverse sear” method for steaks that are greater than 1 inch thick

Thick cut steaks, like a Tomahawk, Ribeye or Cowboy steak need to be handled slightly differently to ensure a crisp crust and tender juicy center.

The traditional hot and fast cooking methods recommend you sear the steak first.

With thicker steaks, you run the risk of leaving the inside cold or scorching the surface just so you can get the center to that perfect medium-rare.https://youtube.com/embed/dEfskLJ9pDQ?feature=oembed

That’s where the reverse sear comes in.

The reverse sear is the usually hot and fast method flipped on its head. You get your steak up to temperature in the oven or on the cool side of a grill set up for two zone cooking, before finishing it over high heat to get that all-important crust.

The reverse sear also works well on steaks with a tender texture but little marbling, like the Tenderloin, as it’s less likely to dry them out.

How to reverse sear your steak:

- Season your steaks and, if possible, leave them uncovered in your refrigerator to draw as much moisture out of the surface of the meat as possible.

- Preheat your oven or grill to between 200 and 275°F.

- If you are using a grill, create a two-zone system, banking your coals, or turning one of your burners to high while keeping the other one low, to create a hot and a cool zone.

- Put your steaks in the oven, or on the cool side of the grill and roast them until they are about 15°F below your target temperature.

- Once the steak hits the correct temperature, take them out of the oven

- If you are using an oven, splash a little vegetable oil in a pan and heat it till it starts to smoke.

- Cook for about 45 seconds on each side until nicely browned.

- If you are using a grill, wait until your steaks are about 10°F below your target temperature, then take them off the heat as they will continue to cook.

Flip frequently

One of the great myths of cooking steak is that, once you get it on your grill on in your pan, you should flip it as little as possible.

The reality is that flipping your steak regularly helps to keep it juicy and cut down on the time you have to wait before you can start shoveling it into your mouth.

Food scientist Harold McGee’s experiments indicated that flipping your steak around once every 30 seconds could cut the cooking time by as much as 30% and help to cook the meat more evenly, preventing one side from drying out.

Salt ahead of time

The conventional wisdom with steaks is that you don’t salt them before cooking. Unfortunately, as with a lot of “common wisdom,” this is way off base.

The best method for seasoning your steaks is to salt them 2 hours before you plan to cook them.

This allows the salt time to mix with the surface moisture of the meat, turn into brine, and be reabsorbed by you steak, spreading the seasoning through the meat.

If you don’t have time to let your steak sit for a day, salt your steaks just before they hit the pan.

Try not to salt them between 5 to 10 minutes before cooking, as the salt will draw the moisture to the surface of the meat, but it won’t have time to evaporate. This excess moisture can ruin your chances of getting a good sear.

Don’t worry about resting steak

Resting, as we’ve all been led to believe, does not improve your steak. In fact, it can actually undo the hard work you’ve put into cooking it.

Resting your steak after it cooks can cause it to overcook through heat carryover, where the meat continues to cook after it’s been taken from the pan, or cause the moisture in the meat to soften you crispy crust, or just get a little cold.

Having said that, don’t stress about NOT resting steak if you need some extra time to get your side dishes ready that’s totally fine too.

Use a meat thermometer

The humble meat thermometer is the greatest tool in a your arsenal.

Testing how done your meat is by touch and sight is never going to be as accurate as using a quick-read digital thermometer and a rise of just 10°F is the difference between rare and medium-rare.

Checking to see if your steak is cooked by comparing it to the texture of your face is, at best, a trick for harried steakhouse chefs and, at worst, just downright silly.

For the best results, when cooking steak, get a good meat thermometer and refer to our temperature guide to steak doneness.

Steak Doneness Guide

- Blue Rare (115°F): Seared on the outside but barely cooked in the middle, a Blue steak is basically still mooing. Much like Well Bone, Blue steak isn’t to everyone’s taste, and the lack of cooking means the center can be very chewy and slightly metallic in flavor.

- Rare (120°F): Just 5°F from Blue we find Rare. Seared on the outside with a bright red center that is cool to the touch. Rare is a good level of doneness for leaner steak cuts where you don’t have to worry about rendering down the fat.

- Medium Rare (130°F): Medium Rare is the king of steak doneness levels. A good Medium-rare steak has a pink center, with just a hint of red, coupled with a crisp brown crust.

- Medium (140°F): Medium steaks have no hint of red, and the meat should be pink and firm all the way through.

- Medium Well (150°F): When it’s cooked to Medium-well, the steak starts to lose most of its water, drying out the meat and causing the fat to leak out.

- Well Done (160°F): Much like blue, most people aren’t going to ask for a Well-done steak, and most people will recoil in horror at the very idea. Remember, if you are cooking a steak Well-Done, you’ll have to cook on a lower heat for longer, to avoid burning the outside.

Steak, the king of meats

If you’ve made it all the way through this guide you are now better informed than 99% of meat eaters.

With a basic understanding of all the different cuts, where to buy them and how best to cook them, you can head off and do a little beef-based experimentation of your own!

If there something we missed off our guide to stake? Are there any basics that you think are vital? Please do let us know in the comments below!